At this point it’s become a relentless drumbeat: Rob Ford wants subways. He wants them so much he’s prepared to spend the next two years campaigning for reelection on the promise of subways for Scarborough — and, if there’s time, maybe for Etobicoke too. Underground trains have become a live-or-die priority for his administration.

Why this is a foolish political play is well-established: Ford is promising something he has no workable strategy to deliver. He’s writing a multi-billion dollar cheque he can’t even begin to cash.

But beyond that, there are more reasons why Ford’s tunnel vision is bad for Toronto. A recently unearthed “secret” report, first publicized by the Toronto Star’s Royson James and then released by Steve Munro, raises a number of objections to the suburban subways at the centre of Ford’s demands.

Here are four of the bigger reasons why Ford’s subways won’t work.

1. Scarborough & North York haven’t become the bustling downtowns planners thought they would be

If you’re looking for proof that now-former TTC General Manager Gary Webster was loyal, look no further than this leaked report. Written in March of 2011, it basically lays out all that is wrong with Ford’s subways-only approach to transit building in the suburbs.

And yet the report — so devastating to the arguments Ford’s been using to support his transit plan — didn’t leak until recently, almost a year after it was originally written and then buried by the mayor’s office. And even then, indicators say that the leak didn’t come from Webster’s office.

The smoking gun part of the report goes like this: Toronto planned its transit expansion back in the 1980s under the assumption that they could limit growth in the downtown core and turn the city centres in Scarborough and North York into bustling job-rich urban spaces. Metro Council and the TTC expected huge job growth in the inner suburbs — projecting a 218% increase in the number of jobs in North York Centre, and a whopping 351% increase in Scarborough Centre.

Those projections turned out to be spectacularly wrong. More than 25 years later, neither North York or Scarborough has seen anywhere near that kind of job growth. The city as a whole has only added about 70,000 net new jobs since 1986. North York Centre added 800 employment positions, while Scarborough Centre actually saw a net loss of employment positions, shedding 700 jobs.

Employment areas and transit ridership are very closely linked. Toronto’s existing subways are so successful because they connect homes with all the big buildings downtown where people work. Most of the new residents in the city’s suburbs, unfortunately, don’t work in areas near where Ford’s subways would go — a lot of them find employment in the 905.

Which means that Ford’s 2012 transit plan is based on planning concepts and ideas from the 1980s. Concepts and ideas that turned out to be wholly and devastatingly incorrect.

2. In the wake of low job growth, ridership projections are much lower

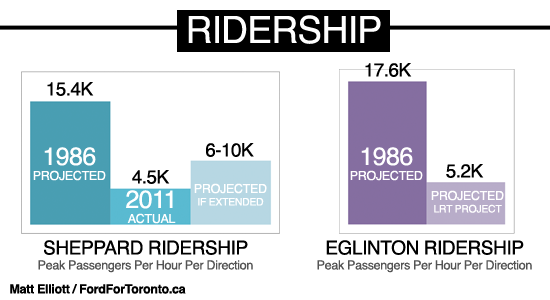

Because these subways likely aren’t going to be of much regular use to the person who lives in Agincourt but works in Markham, the TTC has dramatically reduced its projections for rapid transit routes on Eglinton & Sheppard. The latter was expected to carry 15,400 people in its peak hour. In its abbreviated form, it carries less than a third of that figure. Expectations for ridership on Eglinton have been scaled down by a similar amount.

As of 2011, the TTC estimates ridership of 5,400 people in the peak hour per direction on Eglinton, and 6,000 to 10,000 on a fully built-out Sheppard line from Downsview to Scarborough Centre. About 15,000 riders per hour are needed to justify the costs of a full-scale subway.

3. The subway system costs us a ton of money to maintain — and Rob Ford’s subways would lose money

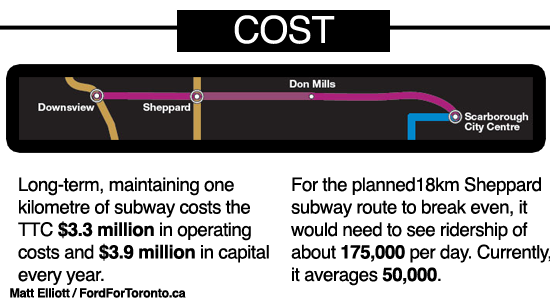

An interesting statistic via the leaked report: the TTC spends $230 million in operating costs and $275 million in capital costs just to maintain the existing subway system. Assuming those figures take into account the costs of maintaining the Scarborough RT, that works out to per-kilometre maintenance costs of $3.2 million operating and $3.9 million capital. In other words: every kilometre of subway costs $7 million a year. Just to keep the trains running.

So much for all this talk of subways being an asset that last 100 years with minimal operating costs.

You can have a lot of fun with these numbers, though it’s important to remember that they represent long-term costs of maintaining infrastructure. Things will be much cheaper to run when the infrastructure is shiny and new.

Still, take the full 18 kilometre Sheppard Subway route the mayor wants to build. Not only will the new track and tunnel cost about $300 million per-kilometre, we can also expect to pay $59 million per year in operating costs and $79 million in capital. Working from the TTC’s assumption that each rider is worth about $2 in revenue, Sheppard would need in excess of 175,000 riders per day to even approach break-even operation.

Because we haven’t seen the job growth predicted in the 1980s, ridership projections don’t approach that break-even point. The city would need to subsidize Rob Ford’s subways for decades to come

4. Given current priorities, Rob Ford’s subways are the wrong subways for Toronto

We run the risk with this subways-and-LRT debate to oversimplify things down to some sort of pseudo-ideological battle. But this really isn’t a matter of choosing sides: you aren’t either for LRTs or for subways. It’s about choosing the right mode for the right route at the right cost.

Let’s make it clear: no one is saying that we should focus only on surface light rail transit. Toronto’s transit future includes new subways. It has to.

There are two pressing issues facing Toronto’s transit system.

First, there’s a lack of higher-order transit connecting the inner suburbs. Mobility sucks across much of the 416 and that limits our ability to successfully address a host of social and fiscal issues.

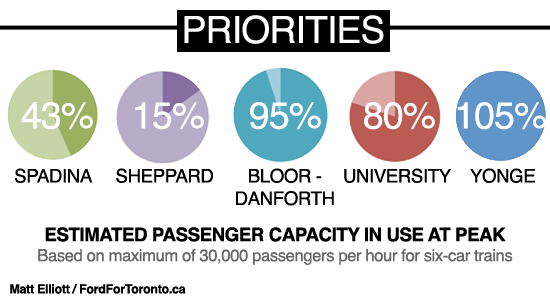

Second, the backbone of our transit system — the Yonge subway line — is overcapacity and trending worse. (Current capacity estimates for Toronto’s subway routes and extension were compiled based on data provided by former staffer Karl Junkin on Steve Munro’s blog. Big thanks to him.)

The city’s current transit planning mostly tries to address the first point. With a network of suburban light rail lines, the TTC can provide service that’s way more effective than the current buses without breaking the bank. Light rail is flexible enough and cheap enough to provide for frequent expansion that isn’t always reliant on provincial funding gifts.

As for the second point: we’ve got nothing. The Yonge subway line operates at more than 100% of its capacity during rush hour, and often even outside of rush hour. Up until now, the TTC has proposed a bevy of short-term fixes like automatic train operation and adding extra cars to the subway trains, but these are expensive band-aids that aren’t going to permanently resolve chronic overcrowding.

No, the only real solution to fixing Toronto’s crowded subway problem is to build another subway.

The Downtown Relief Line, kicked around as an idea since the 1970s, could extend down Don Mills from Eglinton, connect with the Bloor-Danforth line at Pape and then continue on a route through the eastern part of the old city before connecting with the Yonge & University subways downtown. A second phase could take the line on a similar route in the west.

Unlike Eglinton & Sheppard, the TTC’s ridership projections for this route have actually increased since they were first made in 1986. With 13,000 riders per hour in the peak direction, the DRL would open with ridership very close to subway minimums and, more importantly, would serve as a relief valve for the overburdened Yonge line, solving one of the most pressing issues facing Toronto’s transit system. The line would provide new service to dense neighbourhoods while simultaneously having a positive network impact.

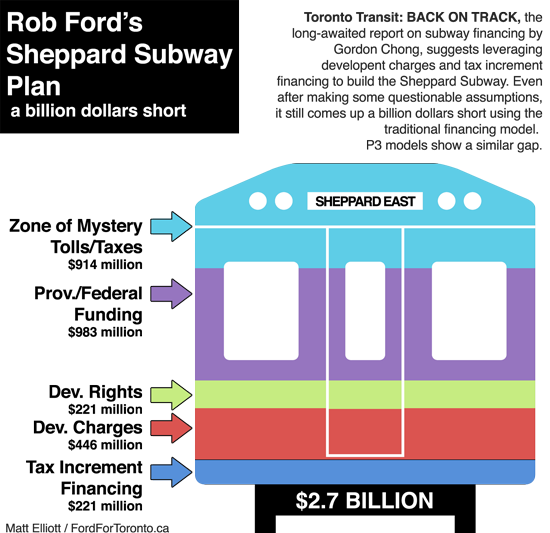

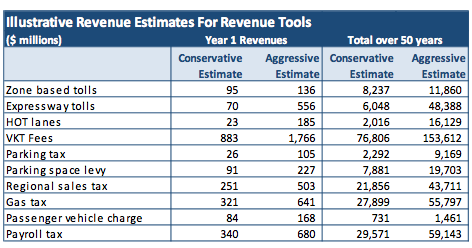

If Rob Ford really wants to champion subways, this is the one he should support. It’s achievable, justifiable and ultimately affordable, thanks to some of the revenue tools put on the table by Gordon Chong.

There is a subway vision that actually makes sense for Toronto — it’s just not the one the mayor is fighting for.