While I was out: Rob Ford experienced yet another spectacular defeat on the floor of council. True to form, the mayor refused to endorse any workable revenue plan for building his beloved Sheppard subway – even the one that came from his council allies. Instead, Ford stuck with what the political strategy that has sustained him since he was first elected councillor over a decade ago: yelling and losing.

Here’s how it happened.

SUNDAY

March 18, 2012

Rob Ford devotes much of the time on his crazy boring radio show toward the transit discussion. As recapped by OpenFile Toronto’s David Hains, the mayor and his co-host Councillor Paul Ainslie hit all the same notes you’d expect: people want subways; St. Clair’s a disaster; all glory to the private sector; and the power of repeating the word subways endlessly.

Notably, Ford and stalwart Ainslie agree that the Sheppard Subway should be funded with “creative financing because people don’t like taxes.” This attitude would continue throughout the week, and sink any remaining chance Ford had of winning the council vote.

MONDAY

March 19, 2012

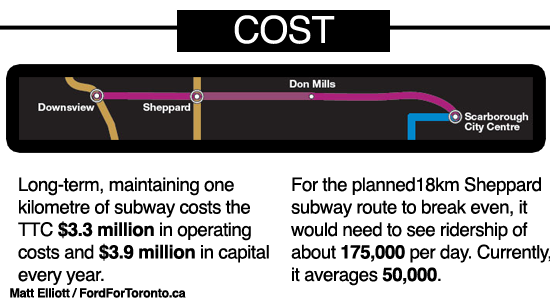

With the special council meeting just two days away, subway advisor and noted dentist Gordon Chong again makes public his opinion that the mayor must support new tolls and taxes if he wants to see a subway extension on Sheppard Avenue. Ford continues to ignore the advice of the man he picked to make the case for subways in Toronto.

Meanwhile, many of the swing vote councillors begin to make their opinions known. Councillor Josh Colle tells reporters he’s just looking for some kind of indication of where the mayor will get the money to build subways. “A pie graph would be nice, just something that would show where the source of funding would come from.â€

But the mayor’s “plan,” even presented as a pie chart, would prove unconvincing. It’d end up looking a lot like this:

TUESDAY

March 20, 2012

More mighty middle voices tip their hat toward the LRT plan. Councillor Mary-Margaret McMahon tells the Toronto Sun’s Don Peat that she’ll be supporting light rail because “Nothing has been concretely brought forward and I don’t see a [subway] plan.” Councillor Ana Bailão also hints that she’ll be a light rail vote.

In a bit of a surprise, Councillor Ron Moeser joins the group of councillors supporting the expert panel’s recommendation for LRT. Moeser has been battling an illness for several months that has caused him to miss virtually all council votes relating to transit. His support for the mayor had been widely assumed, but the mayor may have pushed things too far with the Scarborough councillor.

At this point, a majority of councillors have firmly pledged their support for light rail on Sheppard.

WEDNESDAY

March 21, 2012

Council begins its session by endorsing the use of Skype as a means for Professor Eric Miller to take questions from councillors. Miller was the lead on the expert panel that ultimately recommended the light rail plan. After much debate, Skype finds strong bipartisan support, though the mayor objects.

Soon after, battle lines are drawn. Councillor Glenn De Baeremaeker moves the motion that will support the panel’s recommendations. As a counter, budget chief and Scarborough Councillor Mike Del Grande proposes what we’ve all been waiting for: new revenue tools to fund transit.

Del Grande’s motion includes a levy on non-residential parking spaces, and seeks to raise $100 million per year for transit funding. The proposal is rightly criticized for being light on detail and short on scope. Those kinds of revenues would only fund about 300 metres of subway construction every year.

But, still, the motion is welcome news, acknowledging that even the most thrifty of suburban councillors have recognized the need to build public transit with public money. Del Grande finds support from most of council’s right-wing, but is stymied when the mayor — stubbornly, foolishly, inexplicably — refuses to lend his support to the plan.

Del Grande would end up attempting to withdraw the motion the next day. Without Rob Ford’s support, he knew it was doomed.

In another bit of procedural pettiness, Ford’s allies end the day with a good old-fashioned filibuster. The plan, which nobody expects to work, is to run out the clock and force a continuation to Thursday, with the hope that they can use the time to convince some councillors to support them.

THURSDAY

March 22, 2012

Having exhausted all his remaining options, Ford pulls out a would-be trump card: a loud and rambling speech in which he uses the word “subways” repeatedly. The point, buried in amongst the repetition, was to convince council to delay any decision until after the release of the federal and provincial budgets. The mayor appears to actually believe that those governments – both of whom are in full-on austerity mode – may announce billions of dollars in transit funding for Toronto.

As has become their custom, council mostly ignores the mayor.

The vote happens shortly after lunch, with the results breaking down mostly as expected. With 24 votes in favour, council supports the recommendations of the expert panel for light rail on Sheppard. Nineteen councillors stand opposed. Notably, Giorgio Mammoliti, who had promised on Wednesday that he would fight against the light rail plan on behalf of his constituents, ends up missing the vote on Thursday.

FRIDAY

March 23, 2012

The fallout from the vote comes quick and looks obvious. The mayor declares, yet again, that his election campaign begins today. The plan is to foster so much support for subways that he gets yet another strong mandate from voters in 2014. By Sunday – on his still-boring radio show – the mayor will even go as far as floating the idea of running a slate of Ford-supporting candidates in wards across the city, in the hopes of ridding council of those who oppose him.

This brings to mind two immediate questions:

- Would any legitimate candidate actually want to be part of a slate backed by a mayor with a terrible approval rating and a record of refusing to work with his allies to accomplish anything?

- If Ford’s going to be in full-on campaign mode for the next two years, then who the hell is running the city?

Ford’s stubbornness on this issue has made for even more alienation. Councillors like Jaye Robinson, Peter Milczyn and David Shiner went as far as to publicly question the mayor’s leadership on the transit file. Their comments were tinged with the kind of frustration that comes about when a mayor refuses to support a revenue tool that he recently championed in an editorial. It’s the same frustration that comes when someone ignores advice from everyone, even in the face of overwhelming reason and common sense.

It’s the kind of frustration that comes when the guy you’re trying to help ends up spitting in your face.

Despite protests from the mayor and his brother, this chapter of the Rob Ford mayoralty appears to be over. There’s little chance the province will re-open the subways debate and even less chance that more money materializes for subway construction. As was originally endorsed by Mayor David Miller and council, Toronto will see light rail transit built on Sheppard, Eglinton, Finch and the Scarborough RT corridor. Transit City lives again.