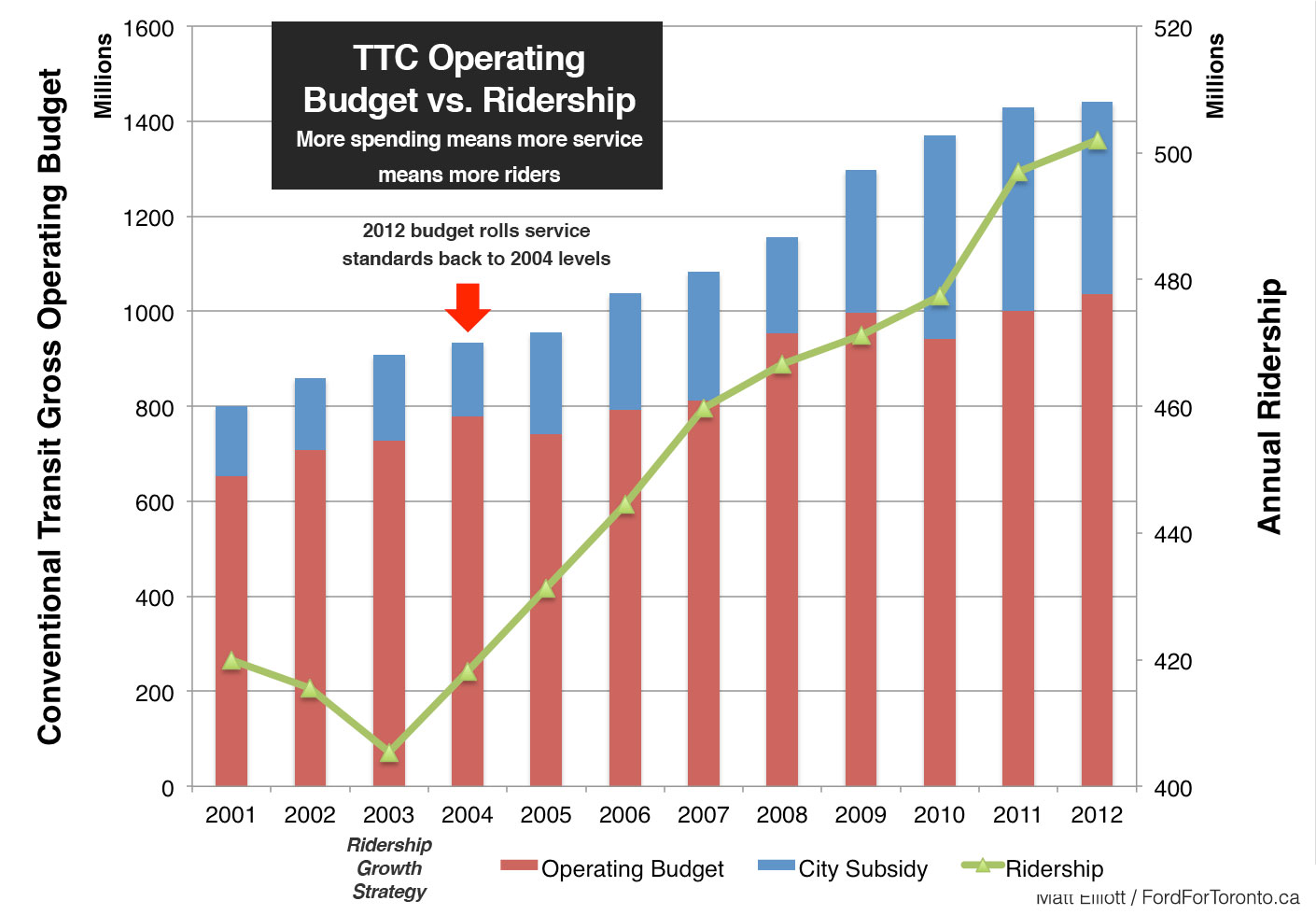

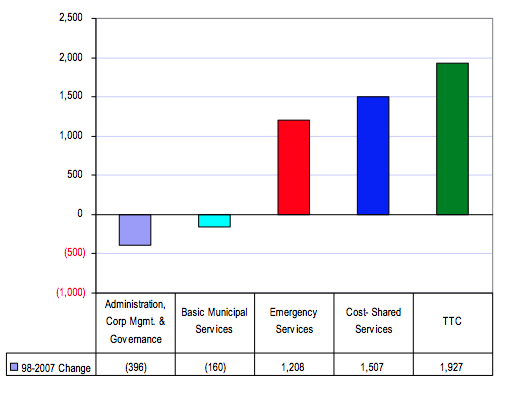

In 2002, the average Toronto resident paid $128.71 on their property tax bill to support TTC operations. In terms of net funding, transit came sixth, lagging behind Police, Housing, Fire, Debt Charges & Social Services. Per capita, transit’s level of financial support was barely above Transportation Services — the department responsible for building roads and maintaining highways. Annual ridership that year was 415 million, down four million from the year before.

By 2011, that same average Toronto resident was now paying $337.95 to support transit. The TTC had transformed into a top priority, now following only the police as the largest recipient of net municipal spending. Ridership this year is estimated at 497 million. The TTC has added almost 100 million annual riders over the last decade.

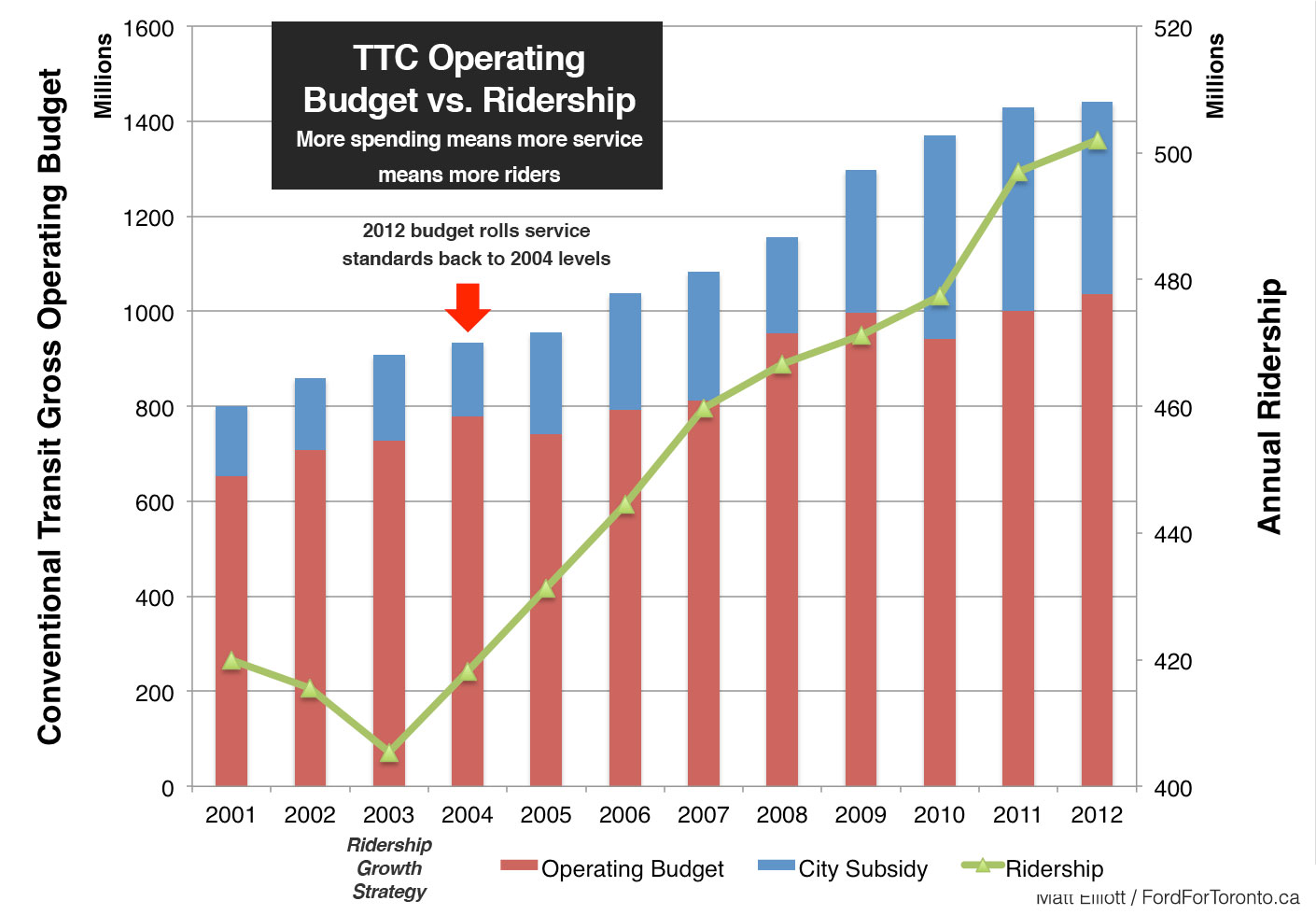

This wasn’t accidental, nor is it an example of out-of-control spending. In 2003, the TTC launched a Ridership Growth Strategy, which was approved by council in 2004. (Voting against: Mike Del Grande, Doug Holyday, Norm Kelly, Giorgio Mammoliti & David Shiner. Rob Ford was absent for the vote.) Representing the first major public investment in transit since the 1980s, the strategy — even if never completely implemented — has seen ridership grow to levels never before seen in Toronto’s history.

More notably, this ridership growth proved resilient even in the face of a weakening job market. What the RGS was successful in doing was creating a climate where more people relied on transit as a primary means of getting around the city. Last year’s TTC budget report described this phenomenon:

Over the long-term, changes in City of Toronto employment levels have tracked quite closely to to TTC ridership changes … However, starting in 2009, City of Toronto employment starting to drop but ridership continued to grow. Only in recent months (January 2011) have employment levels reflected growth over the same period in 2009.

Favourable weather conditions last winter and economic uncertainty for riders have undoubtedly contributed to these strong ridership results. The large service improvements implemented in late 2008 have also prompted the growth as the service on the street more closely matches the service hours of the subway, giving riders far more choice in transit options.

via 2011 TTC Operating Budget (PDF). (Emphasis Added)

The RGS proved that there’s no voodoo required to get people onto transit vehicles. It’s not about marketing campaigns or slogans or incentives. Instead, it’s a fairly simple equation: more spending on more service equals more riders.

For you and I, this might seem like all good news. If these one hundred million trips per year weren’t made by bus, streetcar or subway, a good chunk of them would be made in single-passenger vehicles. Cries of “gridlock” would be even louder. Air quality would be worse.

But for Rob Ford and TTC Chair Karen Stintz, these high levels of TTC usage represent a huge budgetary hurdle, second only to the Toronto Police Service’s continued levels of spending in terms of complexity and overall burden on the City’s Gross Operating Budget.

To save the kind of money Rob Ford wants to save, some of you need to stop taking the TTC.

A Brief History of Transit Travel

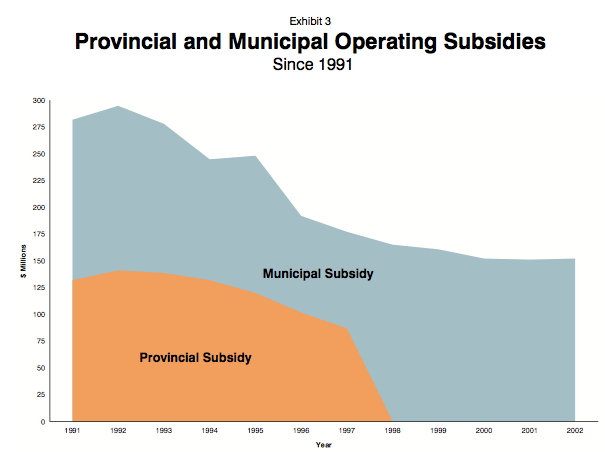

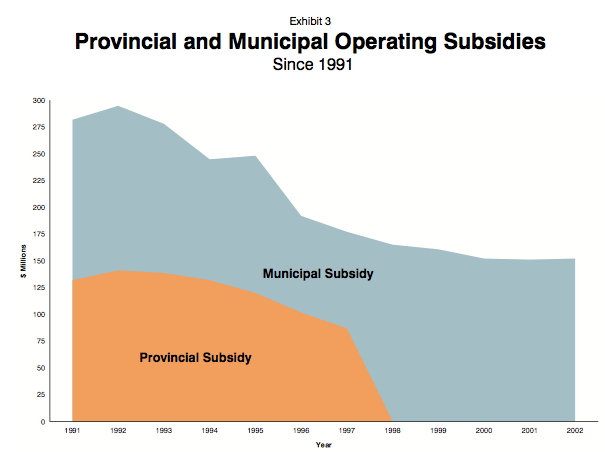

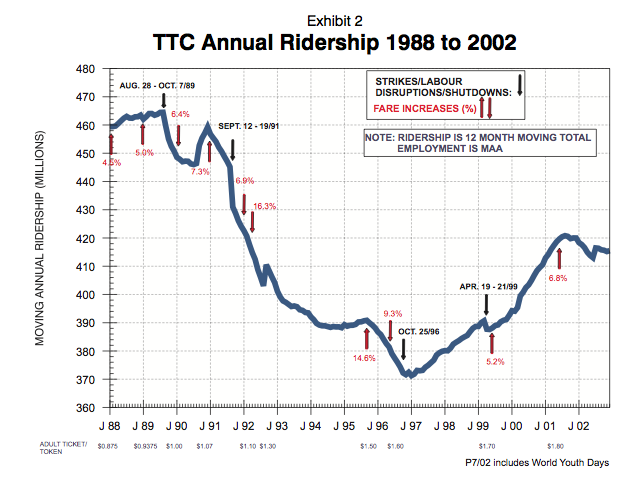

The generally accepted narrative is that the TTC was humming along nicely — and affordably — until Mike Harris’ provincial government swooped in and cut all provincial funding for transit. There’s truth to that story, but it’s an incomplete truth. The reality is that both the province and the city spent the 1990s gradually reducing their respective transit subsidies.

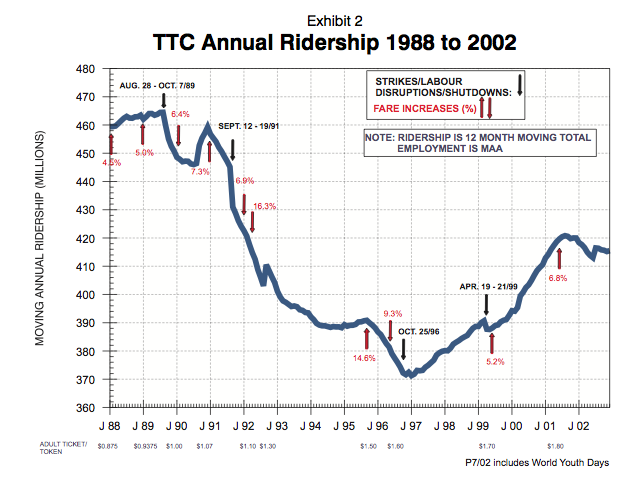

After record high ridership in 1989, ridership began to fall with the Toronto economy. (Two prolonged work stoppages in 1989 and 1991 didn’t help matters.) As ridership fell, so too did public investment in transit, which in turn only caused ridership to decline further. This vicious cycle continued until 1997, when Harris pulled the plug on his share of the subsidy altogether.

Ridership actually sort of recovered following the Harris cuts, but the TTC’s mandate at the time was to improve efficiency, not ridership, and so the gains were a secondary outcome, and ridership was still a far cry from where it was in the late 1980s. It wasn’t until the TTC and City Council made a conscious decision to investment in transit to build ridership that the TTC was able to recover out of its prolonged funk. And while this increase was undoubtedly helped along by external factors — the price of gas, the economy, Toronto’s condo boom — the correlation between the implementation of the RGS and ridership growth is hard to ignore.

What 2012 will do for transit in Toronto

The 2012 budget notes for the TTC lay things out clearly. Referring to the change to loading standards as Major Service Impacts, the document reports that “the TTC will be reversing service improvements implemented by the Ridership Growth Strategy to surface vehicles, causing more crowding and offering less- frequent service on approximately 50 routes during peak periods and 60 routes during off-peak periods.” The change will result in the elimination of 171 staff — most of them drivers — and cause, over the course of the next year, 3.7 million people to opt out of taking trips with the TTC.

Stintz has defended this move, despite it also coming with a fare increase. She released an open letter that makes the following claims: “…you will see minimal change to your bus schedules in January. In most cases changes will be minimal, measured in seconds, not minutes. Some service will be added to some routes in January. No TTC route will be cut. Our system remained intact this March when we told Management to not cut routes. Our system will remain intact in 2012. This does not change the need for funding to preserve service.”

None of these things are particularly true. Talking about “seconds, not minutes” in terms of scheduling is misleading, because what we’re really talking about is having fewer vehicles on the streets picking up people. Some service will be changed on some routes in January, but far more service will be removed. The system did not remain “in tact” in March, especially as many of the promised “service reallocations” never materialized this fall.

She’s right about the last part, though: we could always use some more money to preserve service.

TTC Commissioner John Parker tried to play down the 2012 changes, writing on Twitter that TTC service standards will only be affected “to the extent that we revert to service levels in effect in 2004-05.” But the TTC had 80 million fewer annual riders in 2004. Trying to cram today’s ridership into 2004 service levels is like trying to cram ten pounds of crap into a five pound bag.

It’s easy to hand wave these service reductions. That whole “times are tough – what’s a little extra crowding on a bus going to hurt anyone?” thing. But in real terms, what we’re seeing in 2012 is the reversal of a longstanding successful policy to build transit ridership through public investment in service. By doing so, we threaten to go back on all the progress made over the past decade, setting off a chain reaction where we’ll continually cut spending as service and ridership decline.

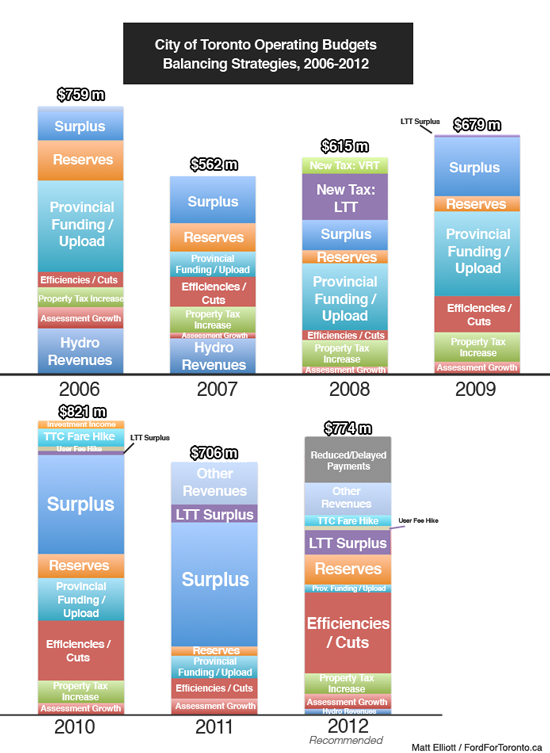

These transit cuts are only necessitated, by the way, because Rob Ford is sticking to an arbitrary 2.5% property tax increase for 2012 and refusing to consider using some of the 2011 operating surplus to balance the coming year’s budget.

As always with transit, this is about priorities.